The realisation that a universal organ simply cannot exist today has long since been accepted. Each piece of music would ideally be played on an instrument that was contemporary with its own time of origin, at least approximately. To play Reger on a Renaissance organ is just as meaningless as to play Praetorius on a symphonic Romantic organ.

A stylistically defined organ may have the disadvantage of one-sidedness, but that is precisely where the attraction lies: in the colourfulness and nuanced detail, which in turn promotes ‘variatio’. Now, the so-called ‘baroque organ’ is not as limited as one might think, especially in comparison to the visual arts, architecture and poetry, and can actually be used in a variety of ways beyond its supposedly narrow boundaries.

In the history of the organ (both in terms of sound and technology) and its music (compositional and genre-pluralistic), the Baroque is and remains a point of culmination, towards which a crescendoing development took place that had a long-lasting decrescendoing effect. Perhaps only once more in the late 19th century (albeit with a different intention: the basic sound, dynamics, symphony of the romantic orchestra) may a similar development have been achieved.

In any case, a well-equipped baroque organ usually contains – in a conservative, positive sense – both backward-looking sounds (e.g. reeds with short cups and aliquots with overtones) and visions of the future (e.g. strings and overblowing registers).

Such an all-encompassing type has been predominant over a longer period of time.

The baroque organ draws on the rich variety of the (late) Renaissance, including the vocal ideal in the singing quality of the principals, as well as the high baroque instruments, which is reflected in many stop names that emulate various ensemble and solo instruments. Therefore, a well-designed baroque organ, apart from its compatibility with contemporary repertoire, easily allows the performance of earlier styles up to the music of the Rococo and early Romantic periods.

This multifunctionality is what makes a baroque organ so attractive, which could be a motivating factor for restorations, reconstructions and new buildings.

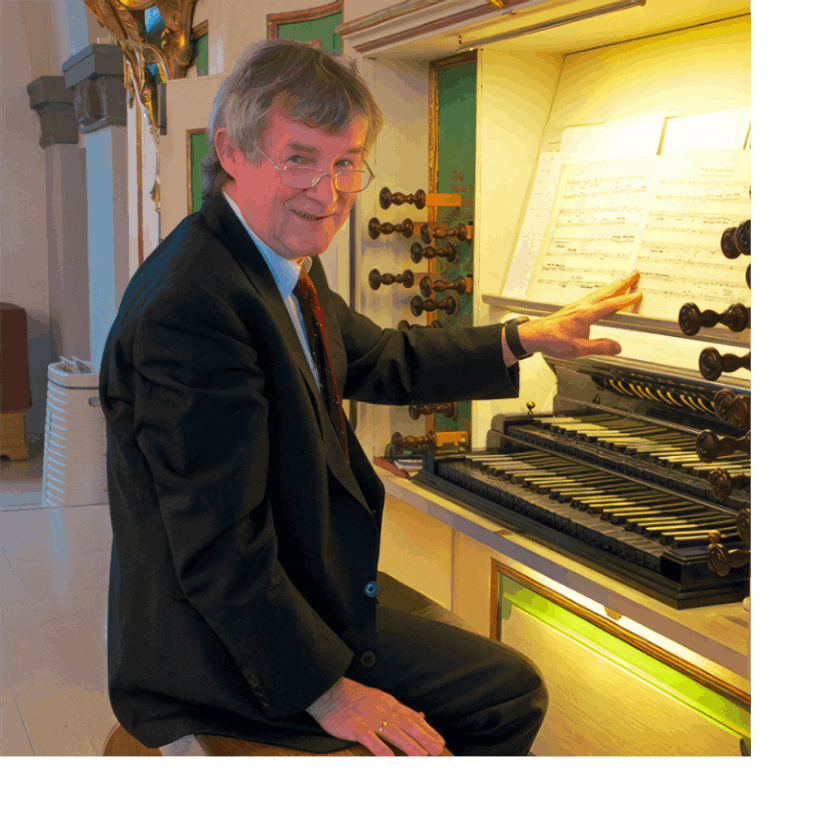

Prof. Klaus Eichhorn, University of the Arts Bremen, 2016